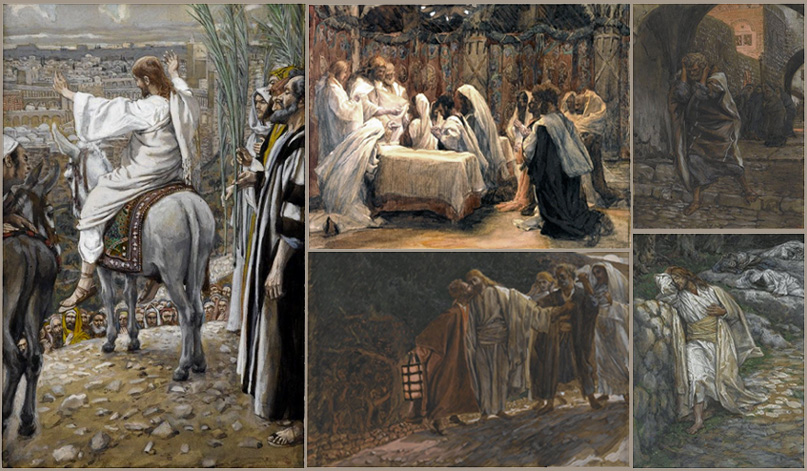

From the Latin Vulgate with Illustrations by James Tissot, 1899

Catholic Harbor presents to you The Holy Week and Passion of Christ Vol. 3 from The Life of our Savior by the Catholic artist historian

James Tissot. This volume covers the span of Holy Week and the Passion of Christ from Palm Sunday through Good Friday morning when Jesus is led back from Herod to Pilot. It includes all of the biblical accounts during this time period in the Sacred Scriptures. This is an opportunity for you and your family to read through the

Four Gospels from the Latin Vulgate along side of the English authorized version

that appears amongst Tissot's master pieces of Sacred Art reliving the

life of Jesus, especially during Holy Week. This is a beautiful addition to the

family Bible and a tremendous aid for meditating on the Passion of Our Lord.

Why I Painted the Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ(An Indulgence of 7 years to the faithful who for at least a quarter of an hour read the Books of of Sacred Scripture as a spiritual reading with the respect that is do the Word of God.) by James Tissot

I wanted to know the truth--to see Jesus of Nazareth as He walked and talked in His native haunts. And then to give back to the millions of my fellow-Christians this real conception of the Founder of the Faith. If I spent ten years in the Holy Land, treading in the very footsteps of the Saviour, it was only that I myself might better realize all that He was, all that He did, before I give it to the world. Day by day, hour by hour, the facts grew dearer to me. I was moved by the consciousness that I was looking at the same rocks, the same trees that had been reflected in the eyes of the Saviour, and as I walked along those paths in which He must have trod, I could not always restrain the tears.

I had studied the Gospels until I knew them by heart, and had located as nearly as I might every act of that Divine One who came on earth to save mankind. It was necessary for me to restore the Temple of Jerusalem in order that I might place the Child Jesus there. To do this properly, I had to study the Talmud of the Jews, as well as the Old Testament, and examine the ruins of the ancient building found beneath modern Jerusalem. To understand the life of Jesus, it is requisite to grasp the civilization of the Jews of this time. All of this I have tried to put into my pictures. Over and over again I visited each sanctified spot. I wandered along the banks of the Jordan and saw the spot where John had baptized his Master. I walked around the shores of Lake Tiberius seeking those rocks from which tradition said, Christ had preached. I saw the spot where Peter's boat had been moored, and at last understood Why He had "gone up into the boat to preach," for the shore was so level that there was no other elevation from which Jesus could have spoken. I have grouped my pictures in several sections, devoted to the "Holy Childhood," the "Ministry," "Holy Week," the "Passion" and the "Resurrection," to avoid all confusion and present the career of Jesus on earth in its natural order. My desire was to make Him live again before the eyes of all men in order that Christians might understand Him better and worship Him more truly. So that the greatest possible number of persons might see and even own the pictures, I have had them reproduced in book form. I have found it necessary to put aside all of the pictures of Jesus painted by the great artists of various ages, not because they were not great paintings, but because they were not the Christ. It is impossible to go back 1900 years in the West and try to reproduce the life of that distant period with accuracy; but in the Orient, where customs change slowly, where progress has been almost entirely unknown, it was not impossible, having before me the descendants of the very people among whom Christ had lived, to paint the pictures of their ancestors. There is not a stroke in my pictures, nor a color, which is not based upon good reasons. If I have painted Jesus in a flowing robe of white, it is because He could have worn no other color, and the all-enveloping garb, tradition states, was necessary if the Christ was to avoid creating the sensation which His shining body would have brought about. I have begun at the very beginning of that marvelous history, when it was revealed to the parents of John the Baptist that he was to be the forerunner of the Messiah. Jesus has been kept too far away from the minds and hearts of men. If by my pen and pencil I have made Him more real to the millions who worship Him from afar, I have accomplished my purpose. The very thing which every Christian most desires--to know all he can about Jesus and His life--has been denied him heretofore. If all men could only know how great was the sorrow and suffering of the "Son of God," devotion to Christianity would be universal instead of partial. It is in the hope that I, perhaps, may be the humble instrument to accomplish something of this work that I have sent my pictures, my life of Jesus, into the world. Introduction to the Passion by James Tissot

The hour ot the Passion is the supreme hour for Jesus; it is for this hour that He came, as He Himself declares in Saint John, xii, verse 27; He speaks of it constantly; He looks eagerly forward to it, for its arrival is to be the signal for the salvation of mankind. This being so, it will be readily understood that this last portion of

my work has been more absorbing than every other, that I have brought to bear on it a yet more minute care in the arrangement of subjects and in the exact interpretation of the facts they recall. Every detail has now an immense value, for it is a portion of the price paid for the redemption of the human race; I have felt, therefore, that not one such detail supplied to us by the Gospel narrative should be omitted, nay, not even one which that narrative justifies us in imagining for ourselves. This is why I have paused at certain subjects which are rarely, if ever, treated, such as Jesus in Prison, The Five Wedges, The Scourging of the Face and The Scourging of the Back, The first Nail, What Our Saviour saw from the Cross, etc. The better to mark the succession of events, to emphasize as much as possible their importance, and at the same time to enable the reader to follow their course with greater ease, I have indicated the chief hours of the sacred drama on a dial which I have several times repeated. Those hours, the passing of which the heavenly hosts must have watched as the most precious and most pregnant with meaning for all time, appeared to me well to deserve to be thus emphasized, and I felt the necessity of gradually, religiously unfolding to the gaze of the spectator each one of the phases of an event the

most solemn in the whole history of the world. I said to myself, moreover, that if the Hour of the Passion was indeed the Hour of Jesus, it would be expedient to reserve for that moment the actual and, so to speak, synthetic representation of His person, such at least as my imagination as a painter and my faith as a Christian should enable me to evolve. Hence the three portraits of Our Saviour Jesus Christ : the principal one representing Him as absolutelv quiescent, the other two: Jesus in Prison and Jesus leaving the Praetorium, shewing Him as the Mediator for and the Victim of men. A few night scenes upon which I naturally came, as it were by the way, were of very special value to me, in that they enabled me to bring out not only more picturesquely but with a more vivid truthfulness that sense of oppression which was so eminently characteristic of all the machinations of the Jews against the Saviour.

One objection has been made to this last portion of my work to which I should like to reply: Too much blood, too many horrors, too many painful and revolting details introduced with a view to producing a heart-rending effect. May I be permitted to remark that those who speak in this way have not understood me. I have already stated what has been my point of view throughout my task: it has been that of an historian, a faithful and conscientious historian. Do people want me to compose an account of the Passion in the style of the poets of the Renaissance? Do they want a well-made crucified figure with a very white skin and three drops of blood at each wound to contrast with the pallor of the flesh? Such a crucified form is not mine, for it is not that of history. Those who are afraid of blood and of wounds, of flesh which turns blue when it is bruised, had better not look at my work and they had better not read the Gospel either. Let me be forgiven for thus bracketing the two together, for each is a work of truth, not of poetic fancy. I attack no one elses theory, I bring no action against any brother artist; every one has his own way of interpreting the same thing, and I can well understand that a point of view very different from my own may be perfectly legitimate; I will even admit, if you like, that it may be absolutely superior, just as an epic poem is, in a certain way, superior to history, but nevertheless history has its value and its rights, indefeasible rights, against which no false delicacy can avail anything. I suspect, moreover, that the criticism I have first quoted is bound up with another already passed upon me: "There is not" they say, "enough of the ideal in his pictures." But we have got to come to an understanding as to what is meant by the ideal. What is the exact interpretation of that word, which is made to signify so many things? As for me, the ideal is the truth: I understand truth in the sense in which Plato understood beauty, for, according to that philosopher, beauty and goodness are one. The ideal is truth in its completeness: truth of facts, truth in the interpretation of facts and of their higher meaning. Why should I sacrifice the first of these truths to the second? Are they not compatible? Will they not be useful to each other? When Leonardo painted the Last Supper at Santa- Maria-Grazie at Milan, he doubtless painted the truth; but only moral truth as interpreted by him, not actual historic truth. When, on the other hand, some realist or so-called realist, some archaeologist-painter such as is now to be often met with, represents the Last Supper of Jesus exactly as he would that of some Jew contemporary with Our Lord, he may give us more or less historic truth, but he misses moral truth altogether. As for me, I have tried as far as possible to combine the two. I wished my Christ to be a true Christ, that is to say, a God-Man as truly Man as He is God, and, again, not a mere ordinary man, but just the Man and no other revealed in the Gospel to every one who reads it with an unprejudiced mind. In thus treating my subject, in so far at least as I have succeeded in my endeavour, I could not miss the ideal, for the true Christ is the realization of the ideal: what good would it have been, then, to distort facts with a view to giving them a kind of factitious ideality very inferior to that which is already innate in them? According to my idea, it was far better to confine myself strictly to the truth as far as that truth is accessible, and this is the kind of ideal which it has ever been my aim to attain. Whether I have or have not attained it, it is not for me to determine. I make but one claim: that my intention was good, and if the result is not approved of, the blame must be laid on my hand alone.

To download the entire book, click on the link below.

Download the book, "The Life of Our Saviour Jesus Christ"

http://catholicharboroffaithandmorals.com/ |